A new wave of research is uncovering cutting edge therapies for the treatment and management of epilepsy in Australia and overseas.

Innovative research by Professor Adam McCluskey and his team at Newcastle University seeks to develop anti-epileptic drugs by inhibiting the proteins responsible for triggering the release and recycling of chemical signals that lead to seizures. Meanwhile new findings in the field of medicinal cannabis has shown a reduction in paediatric epileptic seizures for patients prescribed Cannabidiol (CBD) the active compound in cannabis.

Australian State and Federal legislation, however, may inhibit the access to some therapies for the estimated 250,000 Australians living with epilepsy every day.

Health industry leaders, not for profit groups and patient advocates came together at a recent event hosted by William Buck to learn more about the development of new drugs from Professor McCluskey. Dr Teresa Nicoletti, a Partner at Piper Alderman at the time, but now a Partner at Mills Oakley spoke on the Australian regulatory environment in relation to cannabis producers.

The epileptic drug revolution

The Australian Cancer Research Foundation Centre for Kinomics flow chemistry laboratory based at The University of Newcastle is a world-first research facility, arguably second only to the CSIRO lab in Melbourne. It’s here that Professor Adam McCluskey together with Phil Robinson from the Children’s Medical Research Institute (CMRI) are developing drugs to tackle epilepsy.

A medicinal chemist, McCluskey’s research focuses on the key signalling proteins in the body responsible for biological functions. Studying these proteins, known as GTPases, McCluskey and his team aim to find the keys to each protein to either ‘unlock’ the protein to create a biological function or ‘lock’ the protein to inhibit a specific function. The ‘keys’ identified are the foundations of new drugs.

In the case of epilepsy, the protein being targeted is Dynamin 1. Dynamin 1 is responsible for recycling synapses in the body. For epilepsy sufferers this recycling process occurs at a much higher rate than the general population causing seizures. By identifying the key to unlock Dynamin 1, the team has been able to modulate the protein to reduce the rate of synapse recycling and either prevent or reduce the severity of seizures.

While still at the laboratory stage, animal studies, the discovery of Dynamin 1 inhibitors as an anti-epileptic drug promises future relief for epileptic patients. What’s particularly exciting is the relative efficiency that the Centre for Kinomics has achieved in identifying the inhibitors. Using computer modelling, the lab has been able to profile thousands of chemical compounds and test their effectiveness in inhibiting proteins in a virtual world. When you consider that for a single drug to go to market pharmaceutical companies test over 10,000 compounds, the ability to synthesise compounds in a virtual environment can be cost effective, create a better yield and minimise variability.

In the current environment, the Centre for Kinomics will not be able to bring these innovative drugs to market but are looking to leverage the work undertaken by large pharmaceutical companies in order to commercialise and make them available.

Cultivating Medical Cannabis now legal but therapeutic remedies not yet available

Businesses across Australia can now apply for a license to legally grow cannabis for medicinal purposes. However, it could still be some time before a fully functioning system is in place to provide patients access to cannabis and cannabis-related drugs to ease their suffering.

Dr Teresa Nicoletti, Partner at Mills Oakley believes that it’s Australia’s complex regulatory framework that is preventing patients with epilepsy and other serious illnesses from accessing life-changing therapies available in other countries.

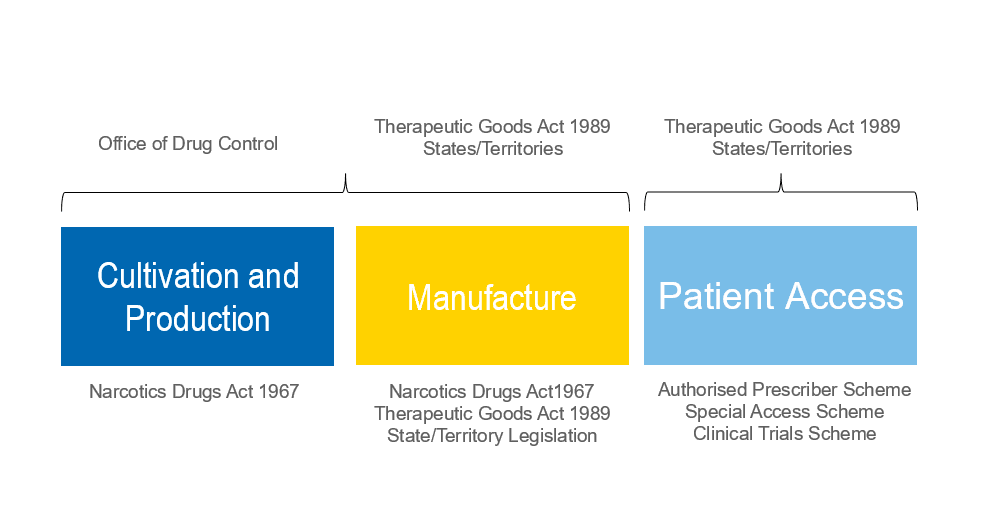

Cannabis is a highly regulated drug in Australia and its use and supply is controlled by a number of Commonwealth, State and Territory laws. The regulatory framework spans three different levels as shown below.

Following amendments to the Narcotics Drugs Act 1967 which came into effect on 30 October 2016, businesses may now apply for a license to grow cannabis for medicinal purposes. However, the requirements for obtaining these licences are onerous and it appears that to date only two licences have been granted for cultivation and production of medicinal cannabis.

Among other requirements, Dr Nicoletti says applicants must be able to demonstrate that they and their associates meet a stringent fit and proper person test, that high security arrangements will be in place and that suitable contracts are in place with harvesters, manufacturers and research organisations.

Essentially, potential cannabis cultivators will be required to provide evidence of an end-to-end supply chain down to the demand for the finished product.

In addition to the licence, cultivators will also be required to apply for an annual permit which specifies the quantity and the specific strains of cannabis they may grow.

Greater roadblocks exist in terms of patient access to cannabis cultivated or produced under the above licences and permits. Generally, once a drug has been approved under the Authorised Prescriber Scheme or the Special Access Scheme, doctors may prescribe it to their patients. This is not the case for medicinal cannabis.

For cannabis and cannabis-related drugs, it remains up to the states to decide whether the drug is allowed, who can use it, dispense it, who will be able to approve it and what dosage is appropriate. This is where things become murky for both cultivators and prescribing doctors.

While the Federal Government has amended the Narcotics Act, local governments are struggling to keep up. As it stands, the permitted use of cannabis differs across each state and territory.

- In New South Wales, medicinal cannabis can be prescribed only by doctors specifically authorised by the state health department.

- In Victoria, medicinal cannabis can be prescribed in limited circumstances by authorised medical practitioners for defined patient groups.

- In Queensland, with specific approvals from Queensland Health, specialists should be able to prescribe medicinal cannabis for certain patient groups, and general practitioners should be able to prescribe medicinal cannabis to individual patients.

- In Western Australia, South Australia and the Australian Capital Territory, doctors are permitted to prescribe locally-produced medicinal cannabis under the strict conditions which apply to other Schedule 8 drugs.

- Tasmania is developing a Controlled Access Scheme to allow patients to access unregistered medical cannabis which is expected to come into effect this year.

- The situation in the Northern Territory is unclear.

The additional levels of approval around the prescription and use of cannabis and cannabis-related drugs enforced by the states and territories do not apply to any other drugs in Australia including morphine and oxycodone.

While the recent announcements by the Federal Government are a step in the right direction, Dr Nicoletti foresees that it will be some time before cannabis is a legally viable therapy for patients suffering from illnesses such as epilepsy. In the meantime, patients and the parents of patients often have no choice but to travel overseas to access prescribing doctors or purchase cannabis on the black market.